“The Food Co-op is Expensive”

by Jon Steinman, Author, Grocery Story: The Promise of Food Co-ops in the Age of Grocery Giants

An intriguing heading to an article, isn’t it!

Probably because you’ve thought it, heard it, or at one time or another, engaged in a lively debate about it.

Me too.

I’ve visited over 175 communities that are home to a food co-op, and have heard this sentiment echo in every one of them.

“The food co-op is expensive”.

So, what about this proposition?

The Power of Perception

When comparing prices between grocers, some items are certainly more expensive while others are cheaper. Food co-ops are no exception. However, food co-ops appear to receive a more consistent and firmer stamp of price disapproval.

Is it warranted?

I believe the answer lies in perception – what we perceive, and to what degree we’re willing to unpack and broaden those perceptions. Food prices are an interesting place to explore this. Food is deeply personal, and not surprisingly, beliefs around food are, hmm… ‘impassioned’.

As a former board director of the Kootenay Co-op in British Columbia, my interest in this topic became more pronounced in the months and years following the opening of our newly constructed store in 2016. After 25 years operating in less than 5,000 sq. ft. of retail space, our 1975-era food co-op had grown into a shiny 12,000 sq. ft. grocery store. The familiar aroma that welcomes any customer through the doors of any food co-op was replaced with the aroma of ‘new’. The also-familiar yet disorienting store layout (a byproduct of 25-years of growth in a building designed as an auto shop) was gone – replaced by wide aisles and more spacious conduct among shoppers. This was thrilling to some, but apocalyptic to others. At dinner tables and on social media threads, it became commonplace to hear “the co-op has become Whole Foods,” or “the co-op has sold-out.” But most common of all? “The food co-op has become more expensive”.

Nothing could have been further from the truth.

Despite a substantial increase in product variety and lower prices thanks to improved economies of scale, many remained convinced – shopping at the co-op had become more expensive. After all, everything was so clean!

This intrigued me – the power of perception to shape one’s relationship to food prices, affordability, and to their food co-op. Equally intriguing – how change, groupthink, and social media can influence one’s food price position.

But perception is only part of our relationship to price. There’s also data.

Co-ops and Competitive Pricing

How do prices at food co-ops compare to the competition – namely, the grocery giants? Smaller stores certainly have a harder time competing with a Costco or Walmart nearby, but most co-ops (including some small ones too) are highly price competitive.

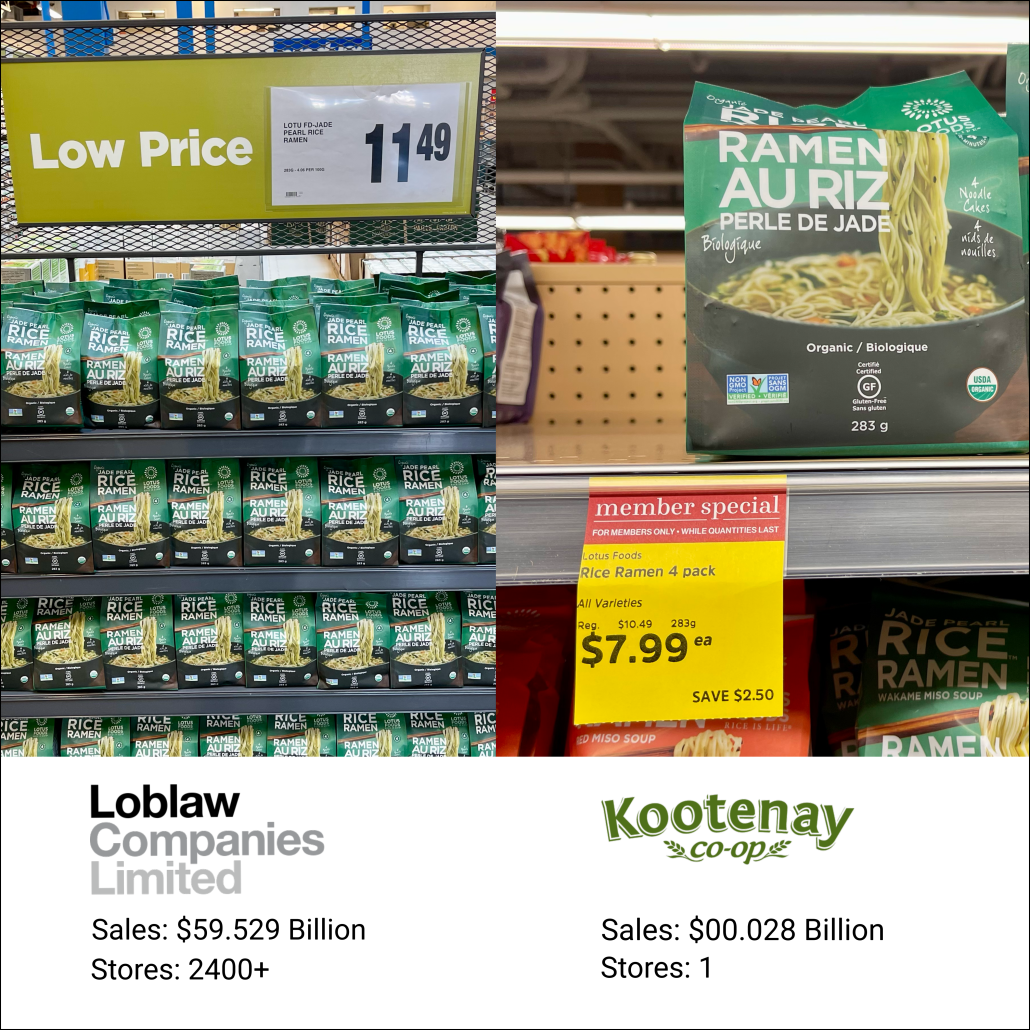

Take Kootenay Co-op. At only 12,000 sq. ft of retail space, the co-op is tiny compared to the average 40,000 sq. ft. grocery store. One might reasonably expect that such a small store would have little chance of competing with Canada’s largest – Loblaw – who operates a store just down the road. Kootenay Co-op’s annual single store sales of $28 million are almost imperceptible to Loblaw’s $59 billion generated by its over 2,400 corporate and franchised locations. And yet, price comparisons that I and the co-op have conducted separately, have revealed comparable pricing on identical products to its three nearby grocery giant competitors. More often than not, co-op prices are lower. In one instance, Loblaw was selling Lotus brand organic ramen nationwide for the “Low Price” of $11.49 (see image). At the Kootenay Co-op? On sale for $7.99 (reg. price $10.49). Loblaw certainly appears to be in the perception business! Examples such as these are commonplace.

Author Jon Steinman regularly conducts price comparisons at food co-ops and national chain grocers. [Photo: Jon Steinman]

Community Food Co-op in Bellingham, WA, has also pursued a regular practice of comparing prices with its major competitors (Kroger’s Fred Meyer, Amazon’s Whole Foods, and Albertson’s Haggen). Once again, the food co-op remains highly competitive and publishes its findings. SEE THE COMPARISONS

What Are We Really Comparing?

Claims that food co-ops are more expensive than other grocers often stem from comparisons of apples to oranges. Most food co-ops prioritize local, organic, or more ethical products, which are often priced higher than conventional, mass-produced alternatives. For example, a farm-raised salmon filet is usually cheaper than its wild counterpart, but they are fundamentally different in terms of quality, sourcing practices, and ecological impact. Both are “salmon,” yet the production and harvesting methods diverge significantly. Without further inquiry, a store with a no-farmed-salmon policy might quickly be labeled as an “expensive” store simply due to its commitment to wild-caught fish. The same applies to organic versus conventional eggs, fair-trade coffee versus mass-market brands, or fresh-baked artisan bread versus industrial loaves pumped with preservatives.

The issue is not simply that food co-ops are “expensive”, but rather, members and customers are comparing non-identical products.

However, food co-ops are in no way synonymous with “organic”, “local” or “ethical”. Food co-ops are in the business of serving the needs of their members and communities. Take Willy Street Co-op in Madison, WI – a successful 1970s-era co-op with three locations. As the only grocer in the north end of the city, the co-op offers both conventional and non-conventional foods. Campbell’s soup at $1.99 is displayed beside Amy’s organic at $4.79. These options are what the community wants from their co-op, and the co-op delivers. This might be the most important distinction to draw in the “food co-op is expensive” story – food co-ops are whatever their communities want them to be. If we want our food co-op to be a “living wage” grocery store that prioritizes the economic welfare of workers above all else, the food co-op can become that, but prices will need to reflect that priority. Want the cheapest possible food at whatever the externalized costs? A food co-op can become that too. Herein lies the dance. Most food co-ops are balancing a dizzying array of priorities, values, and member expectations, all the while making an effort to remain competitive and keep prices accessible.

What Food Prices Pay For

As owner-customers of a food co-op, our purchases, requests, and votes shape the future of our co-ops, our communities, the lives of farmworkers and foodmakers locally and globally, and they shape our planet.

For this reason, we must exercise particular caution when we exert downward pressure on prices. We exert this pressure through what we purchase and where we purchase it, and we also exert pressure through the narratives we participate in, such as “the food co-op is expensive” proposition. I invite ‘caution’, because when we exert downward pressure on prices, we risk challenging a food co-op’s efforts to support its employees and the many other people and groups a food co-op is in the business of serving.

Thankfully, whereas longstanding efforts by food co-ops to preserve fair prices for people and planet have often required a larger expense at the checkout, those efforts may be starting to bear financial fruit. As food prices rise and become more volatile due to extreme weather events, drought, geopolitical instability, trade wars, and risks of centralized and oligopolistic supply, I’m seeing more stable and lower pricing coming from local and regional supply chains. This is no surprise. When centralized systems are stressed or collapse, prices increase. For this reason, where we spend our food dollars and what we spend them on, is not an “expense”, but an “investment”. Food co-ops have long been in the investment business – they’re our diversified grocery portfolio managers. The less integrated our food co-op’s supply chains are to the dominant ones, the less shocks we will experience at the checkout.

Now, more than ever before, is a good time to ask if there really is such a thing as “cheap food”?

Who’s Pricing the Products?

The century-old “low price”, “cheap food” culture, has certainly left consumers with less wiggle room to spend more. But it’s also programmed shoppers for battle. “How can I win? How can I beat the grocery store?” This appears to be the dominant relationship to grocery shopping. “The store is trying to take my money, ergo, I will take as much product as possible for the fewest dollars.” From mobile phone providers to airlines, gas stations, or groceries, the dominant buyer-seller consumer relationships are often rooted in this same win-lose orientation – in distrust. But co-ops are different. Co-ops can’t profit off of their customers. Profits at food co-ops are returned back into the co-op, or into the pockets of customers and workers. If the co-op does well, everyone does well. This completely removes a key determinant of price perception – greed. It can’t exist at a co-op. This alone has the power to transform our relationship to food co-op prices. It certainly has for me. When I recently noticed Que Pasa brand tortilla chips on sale at my co-op for a remarkably low price, I didn’t see it as a gimmick to lure me in, but a reminder that right there in the store, behind the scenes, are staff trying their best to support their employer… me… (you)! The store wasn’t trying to win, nor was I. Embedded in that price, I could see that the store and its staff genuinely cared about me. They care because they too shop at the store. They too live in my community.

It’s in moments like these when “The Food Co-op is Expensive” proposition appears to be much less about price, and much more about perception. While we might not hold much power to change prices, we hold all of the power over our perceptions.

Lo and behold, almost ten years since our new shiny store opened its doors, my co-op has not sold out to Jeff Bezos and become a Whole Foods, the familiar food co-op aroma has absolutely returned, and the aisles appear to get narrower every year.

Next time you preview the sticker price of your favorite yogurt, coffee, or strawberry jam, ask yourself, who and what are you investing in, and how secure is that investment. Those questions are priceless.

Jon Steinman is the author of Grocery Story: The Promise of Food Co-ops in the Age of Grocery Giants (New Society Publishers). He’s an owner-customer and past board director and President of the Kootenay Co-op in Nelson, British Columbia. www.grocerystory.coop